Si l’anglais vous rebute, vous trouverez la traduction française de cet article en cliquant ICI

“I first heard Roky and the Elevators in Houston. I said, ‘Well, that’s it.’ It had a fierce background in R&B and blues, an enjoyably frightening intensity. And then Roky Erickson, one of the finest rock singers since Little Richard [and] Jerry Lee Lewis. His voice was so cutting and fierce and manic. In terms of out-and-out-wildness, it doesn’t get any better.” —

Billy Gibbons (You’re Gonna Miss Me documentary, 2005)

If 13th Floor Elevators frontman Roky Erickson had done nothing but pen the garage-psych classic You’re Gonna Miss Me, he’d still be noted in rock history books. But it turns out that the barreling hit song Roky wrote in 1966 was just a page in a fascinating life wracked by drug abuse and mental illness, and ultimately redeemed by family, friends, and a drive that kept him writing songs through the madness.

Along with a trademark scream inspired by heroes Little Richard and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Roky (pronounced “Rocky”) Erickson had it all: looks, charisma, and talent. The first band to coin the term “psychedelic” in relation to music, the Elevators were musical pioneers and early acid experimenters who recorded two groundbreaking albums, The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators (1966) and Easter Everywhere (1967). (In 1968, International Artists also rushed out a poorly recorded live disc and a final Elevators LP, Bull of Woods, which featured little input from Roky.)

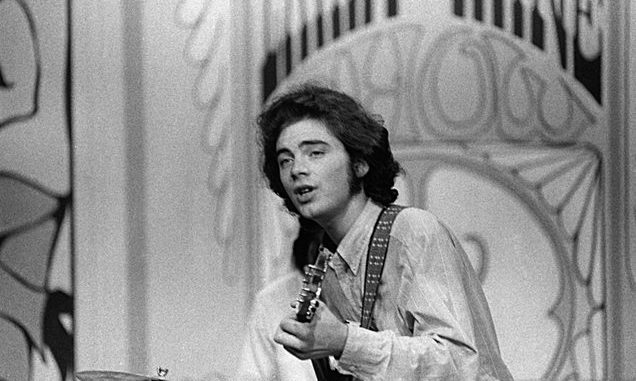

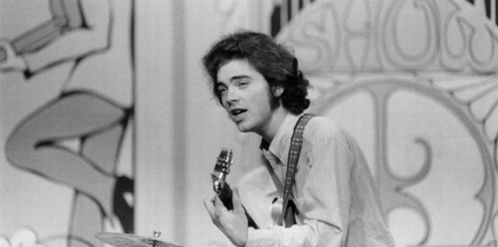

It was during the 13th Floor Elevators’ shows in San Francisco in 1966 that they cemented their reputation—and influence—as short-haired, no-nonsense Texans playing hard driving rock and roll to a crowd of post-folk flower children who’d yet to really turn up. They played with the Great Society (an early version of the Jefferson Airplane) and bands like the Grateful Dead dropped in on their shows. At the height of their brief fame, the 13th Floor Elevators even appeared on American Bandstand to perform You’re Gonna Miss Me. When Dick Clark asked the group who the head of the band was, electric jug player Tommy Hall deadpanned, “We’re all heads.”

It was during the 13th Floor Elevators’ shows in San Francisco in 1966 that they cemented their reputation—and influence—as short-haired, no-nonsense Texans playing hard driving rock and roll to a crowd of post-folk flower children who’d yet to really turn up. They played with the Great Society (an early version of the Jefferson Airplane) and bands like the Grateful Dead dropped in on their shows. At the height of their brief fame, the 13th Floor Elevators even appeared on American Bandstand to perform You’re Gonna Miss Me. When Dick Clark asked the group who the head of the band was, electric jug player Tommy Hall deadpanned, “We’re all heads.”

With their cranked Gibson semi-hollowbodies drenched in reverb the likes of which had never been heard before, the Elevators’ influence on the budding San Francisco scene cannot be underestimated. But by the time the major labels started signing up the Bay Area’s “psychedelic” bands the following year, the Elevators were already back in Texas, unable to tour due to legal problems stemming from drug busts.

The history of the Elevators and how their trip took a dark turn is vividly chronicled in Paul Drummond’s exhaustive biography, Eye Mind: The Saga of Roky Erickson and the 13th Floor Elevators, The Pioneers of Psychedelic Sound. Eight years in the making, the book was released last month and mixes archival interviews and photos with insights from the surviving Elevators (guitarist Stacy Sutherland was shot and killed by his wife in 1978).  Interestingly, Drummond pins the group’s massive ingestion of LSD and search for spiritual truth through music on self-appointed guru Tommy Hall, who joined the band on electrified jug since he didn’t play an instrument. Drummond paints him as having a Svengali-like hold on Roky, who was a mere 18 when they met and had a childlike, malleable personality.

Interestingly, Drummond pins the group’s massive ingestion of LSD and search for spiritual truth through music on self-appointed guru Tommy Hall, who joined the band on electrified jug since he didn’t play an instrument. Drummond paints him as having a Svengali-like hold on Roky, who was a mere 18 when they met and had a childlike, malleable personality.

“Tommy did have an agenda—a vision of the band as the medium for his message,” Drummond writes. “The idea was that the band would take the LSD and then ‘play the acid,’ provoking a synesthesis reaction from the audience.” Drummond writes that, with those early audiences also tripping, no matter how incoherent Elevators shows became the audience seemed to follow them.

But as psychedelic pioneers in a state where owning one joint was a felony, the Elevators―Roky and Stacy in particular―paid dearly. Their plans for a national tour never materialized and the band members’ subsequent drug busts made leaving Texas out of the question.

And then came the 1969 arrest that would change Roky’s life, landing him in the East Texas Rusk State Hospital for the Criminally Insane for three years. Roky wrote a lot of powerful songs at Rusk, but his work was filled with darker images and informed by the vintage horror movie and sci-fi films that he’d loved as a child. After his 1972 release, he became an enormously influential cult artist for his releases both as a solo artist and with Blieb Alien (later Roky Erickson and the Aliens), but his record deals were iffy and the labels increasingly obscure. Royalties were virtually non-existent, even though this era produced one of his most loved albums, The Evil One.

A 1989 arrest for mail theft, along with an addiction to junk mail “free” offers and sweepstakes—Roky was using it as found art, taping it to his walls—landed him once again in a mental hospital.

Musicians and friends never forgot Roky: fellow Texan and Warner Bros. executive Bill Bentley produced the 1990 tribute to Erickson, Where the Pyramid Meets the Eye. The title is a quote from Roky when asked to define psychedelic music―“It’s where the pyramid meets the eye, man.” With artists ranging from ZZ Top, R.E.M., Doug Sahm, and Julian Cope contributing songs to the album, it sparked a renewed interest in Roky’s work. In 1995, Roky fan Henry Rollins published “Openers II”, a complete collection of Erickson’s lyrics compiled and edited by Casey Monahan, with assistance by Roky’s youngest brother Sumner. The book coincided with the release of Roky’s album All That May Do My Rhyme, released by Trance Syndicate, Butthole Surfers drummer King Coffey’s label.

By then, Roky’s lifelong battles with personal demons and mental illness had taken their toll; he was living in subsidized housing and seeing few people other than his mother, who believed in prayer more than medical care. Unable to quiet the voices in his head, Roky kept himself wrapped in a cocoon of white noise―every radio, TV, and sound-making piece of electronics would be blaring at once, while he contentedly watched cartoons. It was a dark period that Erickson slowly transcended through the love and patience of friends, family, and fans.

Today, Roky is back and better than ever, thanks to the efforts of his brother Sumner, former principle tuba player with the Pittsburgh symphony and a musical prodigy in his own right (he now plays with the Texcentrics). It was Sumner who got Roky the medical care he needed and started him on the path to recovery (all chronicled in Keven McAlester’s harrowing Crumb-like 2005 documentary of the Erickson family, You’re Gonna Miss Me). The fact that the musical world was ready for Roky’s return is a testament to the respect of his peers and the timelessness of his music.

Henry Rollins, in a quote in the Austin American-Statesman, said of Roky’s work: “When the real book on American music gets written, he’s [Roky] going to be one of those Mount Rushmore Faces. Guys like Roky make music that amazing place to go. Coltrane and Miles and Hendrix were able to do this. It becomes more than the music and more than the lyrics, a total environment.”

Henry Rollins, in a quote in the Austin American-Statesman, said of Roky’s work: “When the real book on American music gets written, he’s [Roky] going to be one of those Mount Rushmore Faces. Guys like Roky make music that amazing place to go. Coltrane and Miles and Hendrix were able to do this. It becomes more than the music and more than the lyrics, a total environment.”

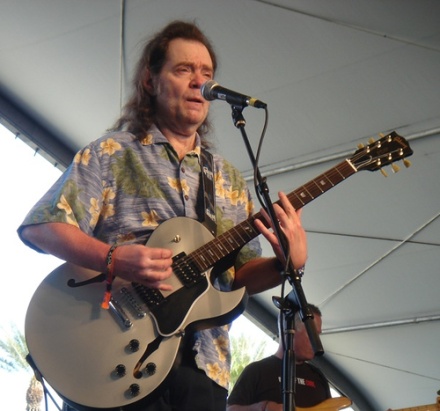

In many ways, 2007 was Roky’s year. He celebrated his 60th birthday in July at home in Austin, Texas with a Friday the 13th gig at the Paramount Theatre, a bigger “rock star” than he’d ever been in his band’s 1960s heyday. With his backing band the Explosives, he also returned to San Francisco, the scene of the Elevators’ first taste of national success, for a triumphant gig at the Noise Pop 2007 Festival. There, he was reunited with Tommy Hall and his wife, Elevators lyricist Clementine Hall. Roky went on to play at Coachella, Bumbershoot, and England’s Royal Festival Hall, as well as his first shows in New York City. Arguably, the high point was his taping for the PBS show Austin City Limits. There, Roky was joined on-stage by longtime friend and fan Billy Gibbons, now slated to produce Erickson’s long-awaited new solo album.

The year also saw the enhanced DVD release of You’re Gonna Miss Me with a postscript the filmmaker and the participants could have never predicted—Roky, under the guardianship of brother Sumner since 2001, regained his full legal rights in 2007 and has weaned himself of psychiatric drugs. He also reunited with his first wife, Dana Gaines, and their son, Jegar Erickson, who road managed a string of sold-out Scandinavian shows for his father.

During the time of his acute mental illness, Roky Erickson had a legal document drawn up declaring himself to be an alien, but in one of the greatest comeback stories in the history of rock, he is once again very much of this earth.

Article et photos reproduits avec l’aimable autorisation de [Gibson Lifestyle]

![]()

2 Rétroliens / Pings